GUNS in SOCIETY

Revolutionary Tool: The Gun and Its Distribution of Power in Art

Addressing Clichés...

While beginning this project, several clichés come to mind in reference to art and history. Clichés include a picture is worth a thousand words and history is black and white. Since elementary school, I have always been presented world history through visual representation, whether an image was adjacent to text in my history textbook or my teacher used images on PowerPoint presentations. Images are ingrained in my understanding of world history and contribute to historians’ records of historical events, but they are generally used as supportive material, in disciplines other than art history. Textual records and written art are arguably studied more frequently than visual art. Theodore K. Rabb and Jonathan Brown’s “The Evidence of Art: Images and Meaning in History” articulate this phenomenon, stating that “verbal often takes precedence over the pictorial in the eyes of most scholars" [1]. The reasons they offer include that scholars often seek answers and conclusions that text is more likely to give, due to its more explicit nature. To address the first cliché, a picture can stir numerous reactions and conversations, but so can written art, “words can sometimes be as elusive as pictures" [1]. This elusiveness is one reason I decided to study examples of revolutionary art work. Written history is often taught as being definitive, whereas art to be ambiguous, but written history is just as subjective as art. Therefore, when art and text are used in conjunction, the effect is a more elusive and thorough understanding. My approach considers the art with its history and I will be using textual evidence as support.

To address the second cliché, one of my motivations for working on this project is to show that history is not in fact “black and white,” but rather if we study it through the lens of art, we may see its true color, meaning, its complexities, inconsistencies, and biases. My art examples are not meant to refute the accuracy of the war, but offer more shades of meaning, that could alter how we understand guns and their place in history. I am relying on Rabb’s premise that “‘artistic images are mental constructs [and] reality too is a construct’” as to challenge the singularity and permanence of historical records [2].

To address the second cliché, one of my motivations for working on this project is to show that history is not in fact “black and white,” but rather if we study it through the lens of art, we may see its true color, meaning, its complexities, inconsistencies, and biases. My art examples are not meant to refute the accuracy of the war, but offer more shades of meaning, that could alter how we understand guns and their place in history. I am relying on Rabb’s premise that “‘artistic images are mental constructs [and] reality too is a construct’” as to challenge the singularity and permanence of historical records [2].

What is Art?

https://www.andertoons.com/art/cartoon/0504/i-dont-think-its-metaphor-for-anything-i-think-its-bowl-of-fruit

https://www.andertoons.com/art/cartoon/0504/i-dont-think-its-metaphor-for-anything-i-think-its-bowl-of-fruit

It seems necessary to address what art is, although this is not the primary focus of this exploration, since I make distinctions between art and text. There is no one answer to this question, like art itself; however, I will provide a few. Art is subjective concerning its value and its meaning, the focus of David Hume’s “Of the Standard of Taste” [3]. According to Rabb and Brown, art is also ambiguous, they state art “by their nature (is) frequently undefined and indeterminate in purpose,” which calls for the need to look at verbal records [1]. This does not mean that art cannot be analyzed independently, but its social meaning and historical relationship acknowledges that art, like written works, does not exist in a vacuum.

Why Should We Study Art?

Art produces strong emotional responses, it stimulates conversations, and educates. Art has often been described by Ancient Greeks and Romans as representing the truth, the nature of reality [4]. Art does provide evidence or meaning of something, but this varies between art works and the intention of the artist. The art that I will be analyzing, paintings and murals of the revolutionary war not only provide evidence for the existence of these revolutions, but they exemplify the subjects of the wars, sentiments of revolutionaries and artists, and perhaps, the brutality and beauty of war. Art has been used to give “answers,” as well as for its aesthetic pleasure “about the universe that they inhabit that are available nowhere else” [1]. In relation to art history, art as artifacts are especially important when other historical evidence is unavailable. The reason I have decided to study art is to determine how and why guns are represented in artwork of revolutionary wars. What does this say about the gun and what does this say about war’s relationship to art? The “disciplinary boundaries” art can cross and which I explore, in terms of race, gender, age, and nationality offer a more comprehensive understanding of history, which is a great defense of art itself [1]. This project will show how revolutionary artworks, mainly paintings, depict guns as symbols of power for the soldiers and civilians who carry them, because of the nature of these images as battles for power. In doing so, guns distribute power among individuals of different identities and become necessary and powerful tools for independence.

What is Art's Relationship to War and Guns?

Rabb’s book, The Artist and the Warrior: Military Through the Eyes of the Masters, states that at a first glance, war and art cannot be more dissimilar, due to war’s active nature and art’s more passive nature. However, war continues to influence artists and this is what Rabb explores in his work. War can be described as an art, in terms of its passion, its motivations, and its strategies. Trained soldiers, like painters or sculptors, use their tools, for soldier’s their guns and for painter’s their brushes, to convey a message. While the impact of a gun, compared to a brush is more immediate and physical, there is similarity in motivation and sentiments. This is especially true of painters, like John Trumbull, an American revolutionary painter who also served in the war and uses his brush to represent the gun.

How Do We Define Guns and What Is the Similarity Between Guns in Revolutionary Paintings?

Revolution may be defined as an exchange of powers that leads to the upheaval and change of a government. David Parker’s Revolutions and the Revolutionary Traditions in the West, explains that “the term ‘revolution’ had been applied to political upheavals from the fifteenth century [and is now] … attached to larger views of historical change which assumed progress.” [5] The idea that progress is always the outcome of revolution is not true; however, revolutions are begun for the belief of progress or at least, a return to stability. Parker uses the terms “rupturing” and “restructuring” to define revolutions, which, although have usually been considered violent, only need to constitute a shift of power relations to be considered a revolution [5]. I decided to select revolutionary war images because of the similarity between the nature of guns and the nature of revolutions with respect to power. The guns in my revolutionary artwork examples show how guns distribute power among the figures that hold them, giving temporary authority to even the lower-class citizen. Guns were often used in history as gifts, which signified the power of the state or kingdom that had them. Guns are also still used for defense and are threatening in their ability to destroy; this has allowed governments to siege nations and for civilians to overthrow their states. In fact, the first recorded use of handheld guns was in 1439 in a battle between Bolognese and Venetians [6]. While guns were originally viewed as a “‘cowardly innovation’” they soon came to be the ultimate intimidator and sign of power in war [6]. This revolutionary object transformed wars and I will show how guns become necessary to revolutionaries who seek basic rights. In most of the paintings I will describe, both conflicting parties, whether it’s the government and citizens or two nations, have guns, which allows both groups a fair chance at war. If a battle is between a government and its citizens, the government is arguably better trained; however, guns in the hands of citizens instills confidence to attempt war. The fear of the common people having the power to overthrow the state with guns is a real concern and in the 15th century, with the rise of guns, England’s government “outlawed the use of guns by commoners… [and also] discouraged their use of bows in arrows” [6]. Where guns specifically distribute power is among individuals of different classes, races, and genders. What I will now show is how revolutionary artworks depict guns as symbols of power for the soldiers and civilians who carry them, because of the nature of these paintings as battles for power. In doing so, guns distribute power among individuals of different classes, races, genders, and parties and become necessary and powerful tools for independence. In addition, I will show how the guns are not the focal point of these images but are central to the identity of the figures, as soldiers. I also explore the painters and muralists whose political affiliations and motivations affect the content and tone of the piece. The role of the artist complicates the historical accuracy of the works and the meaning of the gun.

Method

The artworks, mainly paintings, I selected all depict revolutionary battles and include guns. These paintings vary based on content, artist, time of creation, and victors, although they depict active war scenes. I chose artworks that provide a snapshot of war, where guns would be most prevalent. Instead of following Rabb’s approach of analyzing the artists of different artworks for their own sake, I selected historical events, like Flavio Febbraro and Burkhard Schwetje in their book, How to Read World History in Art, and then found artwork to accompany the events [2]. Unlike Rabb, my aim was to find guns in art and evaluate its cultural relevance to revolution.

I chose five artworks of four wars including, one of the French Revolution, one of the American Revolution, two of the Spanish American War, and one of the Mexican Revolution. Four of the five works were created around the time of the wars and by prominent artists; however, I selected one painting from the 21st century for the Spanish American War to show how our understanding of history has evolved and become more inclusive of racial differences. This painting includes the Buffalo soldiers who were otherwise not painted during the 20th century. I chose well known artists so that I could describe how artists’ political affiliations affect how they represent the revolution and how they ultimately shape our understanding of history. I chose a variety of wars to see what connections can be drawn between these revolutions and how guns are represented. For my analysis, I look at the color of the paintings, the tone, the artist, their style, and the historical background of the war. Through these aspects, I will prove how guns give power to their holders, give them an identity, and how guns distribute power. I will also show how guns are represented as necessary tools for revolution.

I chose five artworks of four wars including, one of the French Revolution, one of the American Revolution, two of the Spanish American War, and one of the Mexican Revolution. Four of the five works were created around the time of the wars and by prominent artists; however, I selected one painting from the 21st century for the Spanish American War to show how our understanding of history has evolved and become more inclusive of racial differences. This painting includes the Buffalo soldiers who were otherwise not painted during the 20th century. I chose well known artists so that I could describe how artists’ political affiliations affect how they represent the revolution and how they ultimately shape our understanding of history. I chose a variety of wars to see what connections can be drawn between these revolutions and how guns are represented. For my analysis, I look at the color of the paintings, the tone, the artist, their style, and the historical background of the war. Through these aspects, I will prove how guns give power to their holders, give them an identity, and how guns distribute power. I will also show how guns are represented as necessary tools for revolution.

Examples of Guns in Revolutionary Art

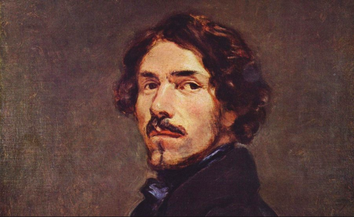

I. Liberty Leading the Revolution, Eugene Delacroix, 1830

French Revolution 1789-1799

French Revolution 1789-1799

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/phaidon-eugene-delacroix-quotes-54446

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/phaidon-eugene-delacroix-quotes-54446

This painting is perhaps one of the most iconic revolutionary paintings, although it produced mixed reactions at its debut in the 1831 Salon, where other French artworks were displayed. Its nationalism and female figure are striking; however, the presence of guns may have been overshadowed if not in the hands of the bare-chested woman.

Artist and Historical Background

Eugene Delacroix was a prominent French painter and was inspired by the riots in Paris that he created this massive painting in 1830 at 8.5 by 10.66 feet [7]. Although fictional, the image was motivated by a real event when working- and middle-class citizens rose the French flag over Notre Dame after protesting for three days, known as les Trois Glorieuses from July 27-29 against Charles X. Charles X’s ordinances of July 26th excluded middle class voters in future elections, suspended freedom of the press, closed the Chamber of Deputies of France, and created new electoral colleges. Intended to preserve the happiness of the people, revolts were incited and Charles X stepped down and was replaced by Louis-Philippe who created a constitutional monarchy. Delacroix’s political beliefs are debatable; however, some scholars have proposed that Delacroix did not directly involve himself in the riots because his patrons were royals [7].

The painting was considered different from other contemporary works because of its blend of realism and idealism. Unlike my other paintings, it is also fictitious. Edith Warren Hoffman’s footnote to the painting states, “We must begin by recognizing the special nature of Liberty Leading the People. This picture is a representation of a contemporary event, but a representation in which realistic accuracy and the telling of the story are secondary to the desire to present the event in an elevated style” [8]. Even Delacroix wrote that the painting is “both ‘a modern subject’ and an ‘allegory’” [8]. The acceptable art form of the time was to avoid complete symbolism or overt heroism that made humans demi-gods; however, Lady Liberty is arguably this kind of figure, contemporaries sought to avoid [9].

Guns in the Painting

The female figure “is not a specific individual Delacroix saw fighting in the streets but rather a personification of the idea of liberty” [7]. This figure has been compared to the Statue of Liberty as well as rulers on Roman coins for her idealized but still human characteristics. The clothing of this figure and others is what represents their social class. The woman wears a “red Phrygian cap, a hat resembling the stocking cap worn by contemporary French workingmen and made popular during the French Revolution as a 'liberty cap' but which originates from antiquity" [7]. While her cap may recall tradition, her power and her appearance point toward the future. Britannica’s article explains that her “modernity is heightened by the Tricolor (the flag) she hoists above her head and the musket with the bayonet she grasps in her other hand” [7] I am most interested in the musket, which is both a symbol of the revolution and previous rioting as well as the power of this Lady Liberty. In other paintings that I explored, excluding my last example of Diago River's mural, this was the only to feature a female figure holding a gun. The addition of being partially nude, symbolizes her sexuality and her dominance, like the gun, characteristics usually attributed to men. A figure just below her and to the left also looks up to her and seems to symbolize the upcoming change in leadership, in which here, the woman leads. The other figures, who are men, are also holding guns, but a variety of different ones. The figure directly to the left of the woman appears to be of a different class due to his top cat and black coat, an indicator that he is of the bourgeoisie. This man holds a hunting shotgun. The younger boy to the right of the woman is “marked as a student by his faluche, a black velvet beret…[and] shouts a rallying call as he brandishes a pistol in each hand” [7]. By having a child hold not one, but two guns, Delacroix comments on the way guns for the pursuit of liberty gives power to even the youngest citizens. The man in the back does not hold a gun, but a sabre, which accentuates the importance of those who do carry guns, like the centermost female figure. Delacroix could have given Lady Liberty another tool, but chose the musket with a bayonet attached, which not only makes her weapon the largest, but arguably the most powerful, because of its dual ability. The power that these guns represent surpasses class and gender, identifiers that otherwise would not have equal power. By portraying figures of different classes, Delacroix not only contributes the revolution to people of all kinds, but also gives them a kind of power that was not apparent in reality. Without the guns, tools used as weapons as evident by the two fallen figures at the ground, the royalists and the Charles X would still be considered the most powerful figures. Instead, the guns have taken down the king, and at the bottom of the image, “a member of the royal army, recognizable by his blue coat and epaulets, [who] lies next to a fallen comrade in the corner” [7]. The guns are represented as a necessary, and common tool in order to achieve liberty. This notion is perhaps, a concretely American one, due to our Second Amendment right; however, it is shared by other revolutionaries.

As I will demonstrate in the following artworks, guns become tied to nationalism and a desire for power changes. In this painting, the French flag is also held by the female figure, leaving the country in her hands. It also suggests that what Delacroix believed was for the citizens, the lower and middle class, to represent the country, not rulers like Charles X. In terms of color and tone, Britannica’s article describes the painting as having “fairly muted colours” and subduing the chaos [7]. The piece definitely has violence, as evident by the fallen figures and the smoke; however, the color and the guns subdue this violence, in order to promote the necessity and positivity of the figure’s desire for revolution. I have seen this piece in the past and never noticed the variety of guns, but immediately saw the flag for its striking red color. That red color never appears on the wounded figures, possibly the result of Delacroix’s style choice, the idealism which masks the realism.

The female figure “is not a specific individual Delacroix saw fighting in the streets but rather a personification of the idea of liberty” [7]. This figure has been compared to the Statue of Liberty as well as rulers on Roman coins for her idealized but still human characteristics. The clothing of this figure and others is what represents their social class. The woman wears a “red Phrygian cap, a hat resembling the stocking cap worn by contemporary French workingmen and made popular during the French Revolution as a 'liberty cap' but which originates from antiquity" [7]. While her cap may recall tradition, her power and her appearance point toward the future. Britannica’s article explains that her “modernity is heightened by the Tricolor (the flag) she hoists above her head and the musket with the bayonet she grasps in her other hand” [7] I am most interested in the musket, which is both a symbol of the revolution and previous rioting as well as the power of this Lady Liberty. In other paintings that I explored, excluding my last example of Diago River's mural, this was the only to feature a female figure holding a gun. The addition of being partially nude, symbolizes her sexuality and her dominance, like the gun, characteristics usually attributed to men. A figure just below her and to the left also looks up to her and seems to symbolize the upcoming change in leadership, in which here, the woman leads. The other figures, who are men, are also holding guns, but a variety of different ones. The figure directly to the left of the woman appears to be of a different class due to his top cat and black coat, an indicator that he is of the bourgeoisie. This man holds a hunting shotgun. The younger boy to the right of the woman is “marked as a student by his faluche, a black velvet beret…[and] shouts a rallying call as he brandishes a pistol in each hand” [7]. By having a child hold not one, but two guns, Delacroix comments on the way guns for the pursuit of liberty gives power to even the youngest citizens. The man in the back does not hold a gun, but a sabre, which accentuates the importance of those who do carry guns, like the centermost female figure. Delacroix could have given Lady Liberty another tool, but chose the musket with a bayonet attached, which not only makes her weapon the largest, but arguably the most powerful, because of its dual ability. The power that these guns represent surpasses class and gender, identifiers that otherwise would not have equal power. By portraying figures of different classes, Delacroix not only contributes the revolution to people of all kinds, but also gives them a kind of power that was not apparent in reality. Without the guns, tools used as weapons as evident by the two fallen figures at the ground, the royalists and the Charles X would still be considered the most powerful figures. Instead, the guns have taken down the king, and at the bottom of the image, “a member of the royal army, recognizable by his blue coat and epaulets, [who] lies next to a fallen comrade in the corner” [7]. The guns are represented as a necessary, and common tool in order to achieve liberty. This notion is perhaps, a concretely American one, due to our Second Amendment right; however, it is shared by other revolutionaries.

As I will demonstrate in the following artworks, guns become tied to nationalism and a desire for power changes. In this painting, the French flag is also held by the female figure, leaving the country in her hands. It also suggests that what Delacroix believed was for the citizens, the lower and middle class, to represent the country, not rulers like Charles X. In terms of color and tone, Britannica’s article describes the painting as having “fairly muted colours” and subduing the chaos [7]. The piece definitely has violence, as evident by the fallen figures and the smoke; however, the color and the guns subdue this violence, in order to promote the necessity and positivity of the figure’s desire for revolution. I have seen this piece in the past and never noticed the variety of guns, but immediately saw the flag for its striking red color. That red color never appears on the wounded figures, possibly the result of Delacroix’s style choice, the idealism which masks the realism.

II. The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, John Trumbull, 1815-1831

American Revolution 1763-1791

American Revolution 1763-1791

Artist and Historical Background

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Trumbull#/media/File:

Self_Portrait_by_John_Trumbull_circa_1802.jpeg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Trumbull#/media/File:

Self_Portrait_by_John_Trumbull_circa_1802.jpeg

Unlike the last painting, this American painting by John Trumbull explicitly shows the violence of revolution and more implicitly, the violence caused by guns. Trumbull’s political beliefs have a more concrete bearing on his work than Delacroix, although both artists’ paintings express support for the revolution. John Trumbull was a prominent American painter who was hired by Congress in 1817 to decorate the Capitol and created this painting, although not included in the building [10]. His patriotism is exemplified in this painting of a historic and actual event and his service in the Continental Army, which led to his nickname, the “patriot artist” [10]. Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts notes that after Trumbull studied in London, he returned to the United States to “immortalize the country’s struggle for independence in a series of paintings based on the critical events of the conflict and thus create to a new iconography for the new nation” [10]. Trumbull was aware of the influence his work would have on history and he connects the relationship between art and war more neatly than either Delacroix or William Gilbert Gaul. He selected the inscription, “‘Patriot & Artist, Friend & Aid of Washington…To his country he gave his sword & his pencil” to be written on his tomb [11]. Trumbull’s commemoration of General Warren, as an American hero, was impactful and led to what Sarah Purcell’s “Martyred Blood and Avenging Spirits: Revolutionary Martyrs and Heroes as Inspiration for the U.S. Civil War” describes as “a familiar nationalist vocabulary that was, in the military context of 1861, used in particularly divisive ways” [12]. Shared memories of the American Revolution, including the death of General Warren were inspirational for the Civil War. This painting has also shaped our historical understanding, especially in solidifying the location of the battle at Bunker’s Hill on June 17, 1775, rather than at Charlestown or Breed’s Hill, which is still debated [13].

The main figure of the piece, General Warren, was intended to be accurately represented and well-remembered although his reputation has been “less well known than Paul Revere, John Hancock, or Samuel Adams” [10]. Warren was a supporter of the revolution, often writing speeches and literature against England. He was also a doctor and accepted a position as General, dying shortly after in battle while still a volunteer. The painting has been associated with historical dialogue, which may or may not have happened such as William Prescott’s order to American soldiers “not to fire until ‘you see the whites of their eyes’” [10]. The presence of historical figures, like William Howe, Henry Clinton, and William Prescott contribute to the realism of the work. Further, unlike Delacroix’s painting, the heroism of the central figure, General Warren, avoids the “demi-God” depiction because he does die. His heroism is also symbolized through his white shirt in comparison to the red of the British.

Guns in the Painting

The presence of guns in this painting distributes power first among nations and then among race, although this is less obvious. British soldiers and American colonists both have guns as the colonists battle for liberty against England. Like Delacroix’s painting, the wardrobe of the figures helps distinguish their allegiance. British soldiers are dressed in their familiar “red coats” and the colonists in more casual garb. Both parties hold muskets, although the British have an attached bayonet, which demonstrates the British army's more skilled and plentiful military, having twice as many soldiers [13]. This scene is in the midst of battle and guns are held in several positions, suggesting their active use. While the British may have been better prepared, the presence of guns gave the American colonists a chance, great enough that they engaged in battle using their weaponry. Like Liberty Leading the People, guns are portrayed as a realistic and necessary tool for independence. Although General Warren died in battle, the painting means to celebrate the struggle of the colonists and the understanding that the colonists not only gave an honorable fight, but they would eventually win in their liberation from England. Although only male figures are depicted in this painting, Trumbull did include two Black figures, “representing the significant participation of black soldiers in the event” [14]. The Black man to the far right is also believed to be a slave. The presence of Black men in war paintings was difficult to find, which is why I will later analyze a contemporary painting, meant to honor Black soldiers. The participation of African Americans was controversial and the Continental Congress placed a ban against Black soldiers and then removed it, when they needed more soldiers. Fear of Black men, especially after they were freed, was intensified by their access to guns. White supremacists and slave owners feared retaliation and “some colonial leaders considered it morally wrong to ask slaves and former slaves to share the burdens of defense” [14]. Some Black men joined the British side believing it would bring freedom; however, others were forced to fight and were used as “substitute draftees…in the North, as state restrictions on the use of black soldiers became even more relaxed” [14]. The Black men who carry the same muskets as their fellow soldiers transcend their status as they too have power with their weapons. On the battlefield, they are equal to their white soldiers; however, this of course ends once off the field. It does not seem that Trumbull meant to commemorate Black soldier’s participation in the battle, but rather create a realistic depiction in which Black men were present.

The death of General Warren is one indicator of the violence of war and the destructive power of guns and yet, the causalities of the battle and the effect of the gun is undermined. The only source of blood, is slight drippings under General Warren’s head and the only indicators of causalities are the General and a few figures who have fallen to the ground. Paintings like Trumbull’s often dilute the intensity of war and of the gun when in fact, “Nearly half of the scarlet-coated regulars who stormed the redoubt fell in the attack, [and] more than a third of the American defenders were killed, wounded, or captured” [12]. Like Delacroix’s painting, the colors of this work are subdued, although the red of the British’s coats is vivid and threatening.

The presence of guns in this painting distributes power first among nations and then among race, although this is less obvious. British soldiers and American colonists both have guns as the colonists battle for liberty against England. Like Delacroix’s painting, the wardrobe of the figures helps distinguish their allegiance. British soldiers are dressed in their familiar “red coats” and the colonists in more casual garb. Both parties hold muskets, although the British have an attached bayonet, which demonstrates the British army's more skilled and plentiful military, having twice as many soldiers [13]. This scene is in the midst of battle and guns are held in several positions, suggesting their active use. While the British may have been better prepared, the presence of guns gave the American colonists a chance, great enough that they engaged in battle using their weaponry. Like Liberty Leading the People, guns are portrayed as a realistic and necessary tool for independence. Although General Warren died in battle, the painting means to celebrate the struggle of the colonists and the understanding that the colonists not only gave an honorable fight, but they would eventually win in their liberation from England. Although only male figures are depicted in this painting, Trumbull did include two Black figures, “representing the significant participation of black soldiers in the event” [14]. The Black man to the far right is also believed to be a slave. The presence of Black men in war paintings was difficult to find, which is why I will later analyze a contemporary painting, meant to honor Black soldiers. The participation of African Americans was controversial and the Continental Congress placed a ban against Black soldiers and then removed it, when they needed more soldiers. Fear of Black men, especially after they were freed, was intensified by their access to guns. White supremacists and slave owners feared retaliation and “some colonial leaders considered it morally wrong to ask slaves and former slaves to share the burdens of defense” [14]. Some Black men joined the British side believing it would bring freedom; however, others were forced to fight and were used as “substitute draftees…in the North, as state restrictions on the use of black soldiers became even more relaxed” [14]. The Black men who carry the same muskets as their fellow soldiers transcend their status as they too have power with their weapons. On the battlefield, they are equal to their white soldiers; however, this of course ends once off the field. It does not seem that Trumbull meant to commemorate Black soldier’s participation in the battle, but rather create a realistic depiction in which Black men were present.

The death of General Warren is one indicator of the violence of war and the destructive power of guns and yet, the causalities of the battle and the effect of the gun is undermined. The only source of blood, is slight drippings under General Warren’s head and the only indicators of causalities are the General and a few figures who have fallen to the ground. Paintings like Trumbull’s often dilute the intensity of war and of the gun when in fact, “Nearly half of the scarlet-coated regulars who stormed the redoubt fell in the attack, [and] more than a third of the American defenders were killed, wounded, or captured” [12]. Like Delacroix’s painting, the colors of this work are subdued, although the red of the British’s coats is vivid and threatening.

III. Spanish American War Soldiers in Action,

William Gilbert Gaul, 1901

Spanish American War, Cuban Revolution 1898

William Gilbert Gaul, 1901

Spanish American War, Cuban Revolution 1898

https://www.oceansbridge.com/shop/artists/g/ga-gaz/gaul-gilbert/self-portrait-107

https://www.oceansbridge.com/shop/artists/g/ga-gaz/gaul-gilbert/self-portrait-107

Artist and Historical Background

Compared to previous paintings by Delacroix and Trumbull, the style of this work is quite different. William Gilbert Gaul was a well-trained painter by 27 through the National Academy of Design and was well known for his military scenes [15]. His impressionistic style, the style of this piece created in 1901, developed from his avant-garde painting students [16]. He was, perhaps, inspired by the Southern landscape, as he painted during his time in Tennessee; however, the location of this painting is unclear. Unlike Delacroix or Trumbull’s art, Gaul does not paint flags, which suggest a more neutral political motivation and patriotism. The focus of this piece is not on the landscape, as with the prior paintings, but on the soldiers and their relationship to their gun. These are the only concrete shapes and are made clearer through their juxtaposition to the ambiguous landscape. The heavy brushstrokes and sepia, a reddish-brown, color create a serious tone, which exaggerates the presence of the gun.

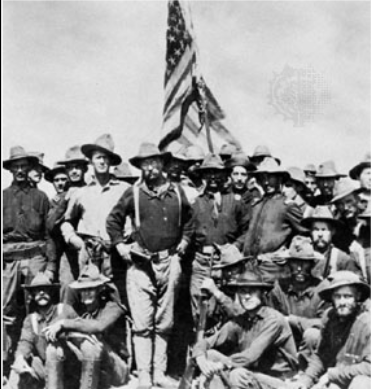

To provide some context to the war, the Spanish American War is described as a “conflict between the United States and Spain that ended Spanish colonial rule in the Americas and resulted in U.S. acquisition of territories in the western Pacific and Latin America” [16]. The war began after the U.S.’s Battleship Maine was attacked on Cuban territory. Cuba had been under Spanish rule and was fighting for its independence. This sentiment struck Congress, as well as the large financial loss the United States’ incurred in the Cuban conflict. Interestingly, the war took place mostly on sea, where the American military greatly surpassed Spain’s. However, paintings, like Gaul’s, do depict battle on land, by Theodore “Roosevelt’s regiment of ‘Rough Riders’ (minus their horses) and the buffalo soldiers of the 9th and 10th cavalries” upon landing on Santiago de Cuba [16]. It may be inferred that Gaul’s painting is of these soldiers, although the specifics are unclear.

Guns in Painting

I selected this painting because of its emphasis on the soldier’s relationship to his gun. The gun defines the man as a soldier and draws a connection to the war. Like the previous paintings I analyzed, the soldier holds a long gun, most likely a musket. His long coat and hat correlate to the time of the war, and his hat suggests he was one of the Rough Riders as seen in this photo below stored in the Library of Congress. The gun, unlike the previous paintings, is not overshadowed by the landscape or action, but is the focal point of the image and creates an identity for the soldier. The man’s gun is also parallel to the turn of his head and both the tip of the gun and his gaze imply a sense of confidence and determination. Here, the distribution of power is suggested, as Cuba’s revolution utilized guns to fight against the Spanish, as well as the United States fight against the Spanish. The guns in this image also contribute to the chaos created through heavy brushstrokes. Unlike the previous paintings, Gaul’s also depicts a bullet being fired on the lower right corner. A cannon may also be evident on the left side of the central figure. Although there is no clear sense of violence, or blood, the impressionistic style allows for a more emotional piece, and I believe a harsher image of war. The distribution of power, across race, that the gun allows is more evident in the next painting of the Buffalo soldiers.

Compared to previous paintings by Delacroix and Trumbull, the style of this work is quite different. William Gilbert Gaul was a well-trained painter by 27 through the National Academy of Design and was well known for his military scenes [15]. His impressionistic style, the style of this piece created in 1901, developed from his avant-garde painting students [16]. He was, perhaps, inspired by the Southern landscape, as he painted during his time in Tennessee; however, the location of this painting is unclear. Unlike Delacroix or Trumbull’s art, Gaul does not paint flags, which suggest a more neutral political motivation and patriotism. The focus of this piece is not on the landscape, as with the prior paintings, but on the soldiers and their relationship to their gun. These are the only concrete shapes and are made clearer through their juxtaposition to the ambiguous landscape. The heavy brushstrokes and sepia, a reddish-brown, color create a serious tone, which exaggerates the presence of the gun.

To provide some context to the war, the Spanish American War is described as a “conflict between the United States and Spain that ended Spanish colonial rule in the Americas and resulted in U.S. acquisition of territories in the western Pacific and Latin America” [16]. The war began after the U.S.’s Battleship Maine was attacked on Cuban territory. Cuba had been under Spanish rule and was fighting for its independence. This sentiment struck Congress, as well as the large financial loss the United States’ incurred in the Cuban conflict. Interestingly, the war took place mostly on sea, where the American military greatly surpassed Spain’s. However, paintings, like Gaul’s, do depict battle on land, by Theodore “Roosevelt’s regiment of ‘Rough Riders’ (minus their horses) and the buffalo soldiers of the 9th and 10th cavalries” upon landing on Santiago de Cuba [16]. It may be inferred that Gaul’s painting is of these soldiers, although the specifics are unclear.

Guns in Painting

I selected this painting because of its emphasis on the soldier’s relationship to his gun. The gun defines the man as a soldier and draws a connection to the war. Like the previous paintings I analyzed, the soldier holds a long gun, most likely a musket. His long coat and hat correlate to the time of the war, and his hat suggests he was one of the Rough Riders as seen in this photo below stored in the Library of Congress. The gun, unlike the previous paintings, is not overshadowed by the landscape or action, but is the focal point of the image and creates an identity for the soldier. The man’s gun is also parallel to the turn of his head and both the tip of the gun and his gaze imply a sense of confidence and determination. Here, the distribution of power is suggested, as Cuba’s revolution utilized guns to fight against the Spanish, as well as the United States fight against the Spanish. The guns in this image also contribute to the chaos created through heavy brushstrokes. Unlike the previous paintings, Gaul’s also depicts a bullet being fired on the lower right corner. A cannon may also be evident on the left side of the central figure. Although there is no clear sense of violence, or blood, the impressionistic style allows for a more emotional piece, and I believe a harsher image of war. The distribution of power, across race, that the gun allows is more evident in the next painting of the Buffalo soldiers.

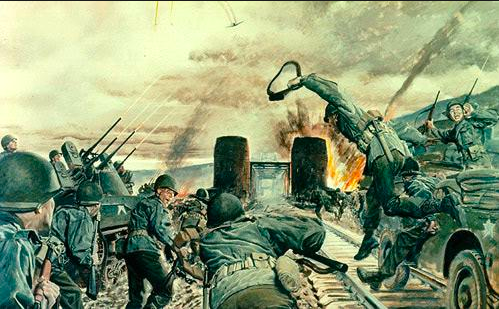

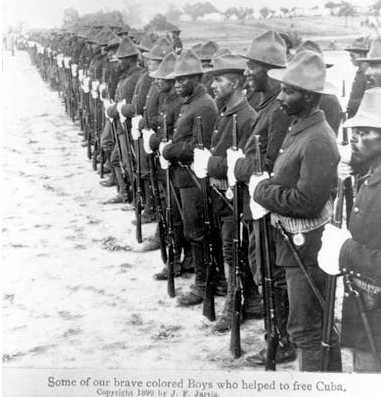

IV. Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th cavalries at the Battle of Las Guasimas during the Spanish-American War

Spanish American War, Cuban Revolution 1898

Spanish American War, Cuban Revolution 1898

https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Spanish-American-War/68989

https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Spanish-American-War/68989

The artist and date of creation for this image are unknown; however, it is stored by the Library of Congress. Unlike Gaul’s painting of the war, this landscape picture includes American and Spanish flags and includes the Buffalo Soldiers, who were Black soldiers of the 10th cavalry regiment of the U.S. army. Despite racial discrimination and the refusal of American citizens, especially in Tampa, Florida “‘to make any distinction between the colored troops and the colored citizens’” they eventually received medals of honor [17]. It was difficult finding paintings that represented these soldiers, although I found numerous modern works and photographs. The reason why paintings of the Buffalo soldiers are uncommon, is possibly because their presence was controversial. It seems that the photographs that were taken were more for documentation purpose than for commemoration or celebration, which is usually the goal of these revolutionary war paintings. This painting distributes power to soldiers regardless of race.

Like Gaul’s painting, this piece shows the guns as active tools and captures bullets firing and smoke, due to its realistic style. This painting is rich in color, which helps distinguish the “winning” party, being the American soldiers. The American soldiers actually take up the majority of the landscape. Some of the tactics of war are included as well as the violence of war, caused by the guns. For example, there are several soldiers lying on the ground and the horse to the right is standing on its hind leg. There is also organization to the fighting, as the American soldier line up towards the back of the image. This tactic of shooting in a line against the opponent was very common, especially in the Civil War. Lastly, there is a man in the center of the image with a horn guiding the soldiers. In the distance, are battleships, which is a reminder of the United States’ true power on the seas against Spain. Several of my examples, like this one, also show soldiers using swords, which was a more traditional tool. The blend of modern and traditional weapons, heightens the innovation of the gun and unfamiliarity with the weapon, which caused mass fatalities.

Like Gaul’s painting, this piece shows the guns as active tools and captures bullets firing and smoke, due to its realistic style. This painting is rich in color, which helps distinguish the “winning” party, being the American soldiers. The American soldiers actually take up the majority of the landscape. Some of the tactics of war are included as well as the violence of war, caused by the guns. For example, there are several soldiers lying on the ground and the horse to the right is standing on its hind leg. There is also organization to the fighting, as the American soldier line up towards the back of the image. This tactic of shooting in a line against the opponent was very common, especially in the Civil War. Lastly, there is a man in the center of the image with a horn guiding the soldiers. In the distance, are battleships, which is a reminder of the United States’ true power on the seas against Spain. Several of my examples, like this one, also show soldiers using swords, which was a more traditional tool. The blend of modern and traditional weapons, heightens the innovation of the gun and unfamiliarity with the weapon, which caused mass fatalities.

V. El Arsenal, Diego Rivera, 1928

Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920

Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920

This example is not a painting, but a mural, Diego Rivera’s preferred art form, done with fresco. The presence of guns in this image is overwhelming and its distribution, both literally and symbolically, is portrayed.

https://www.diegorivera.org/

https://www.diegorivera.org/

Artist and Historical Background

The Mexican Revolution entailed several changes of leadership, beginning with the “call to arms on 20th November 1910 to overthrow the current ruler and dictator Porfirio Díaz Mori” [18]. Díaz ruled through fear and intimidation and suppressed citizens’ liberty to free speech. His interests included industrializing Mexico, which negatively affected the farm workers, and to form stronger relationships with countries like the United States by allocating land. Díaz was overthrown by Francisco Madero but was then replaced by General Victoriano Huerta, who executed Madero. These leaders used the same practice of dictatorship as Díaz, and Madero was succeeded by Venustianio Carranza in 1914. Although there was dissatisfaction with Carranza, he formed a new constitution, which recognized the needs of the people. The country continued in political unrest; however, the end of the Revolution is marked by the creation of the constitution.

The Mexican Revolution entailed several changes of leadership, beginning with the “call to arms on 20th November 1910 to overthrow the current ruler and dictator Porfirio Díaz Mori” [18]. Díaz ruled through fear and intimidation and suppressed citizens’ liberty to free speech. His interests included industrializing Mexico, which negatively affected the farm workers, and to form stronger relationships with countries like the United States by allocating land. Díaz was overthrown by Francisco Madero but was then replaced by General Victoriano Huerta, who executed Madero. These leaders used the same practice of dictatorship as Díaz, and Madero was succeeded by Venustianio Carranza in 1914. Although there was dissatisfaction with Carranza, he formed a new constitution, which recognized the needs of the people. The country continued in political unrest; however, the end of the Revolution is marked by the creation of the constitution.

Guns in the Mural

Rivera’s mural not only responds to the Revolution, but displays his political beliefs. Rivera was a “lifelong Marxist who belonged to the Mexican Communist Party and had important ties to the Soviet Union” [19]. “His art expressed his outspoken commitment to left-wing political causes” and El Arsenal or The Arsenal features the communist symbol of the hammer and sickle. Rivera’s personal beliefs supported the Revolution and, in this mural, the working class has power as an armed collective group. There are several long guns in this image as well as bullets and magazines. Guns are being distributed from the box on the bottom of the image and are being carried out of this arsenal. This image implies that guns were a necessary part of the Revolution to ensure the working class became heard. Like the organized militaries of the Americans and British, these Mexican revolutionaries have power in numbers and through their secretive supply of weapons. The distribution of power also extends to women and children, who have as much of an involvement in the war as their male counterparts. Like Delacroix, a child is also helping spread the guns and symbolizes the future of Mexico. It seems that Rivera is also implying the importance of the artist in war. He includes Frida Kahlo, a contemporary Mexican artist, in the center of the mural, who also holds a gun. The role of the artist extends beyond the artwork and sometimes even in the physical war. Rivera’s murals were often created in public spaces, so that they may be accessible to the common people. Not only was the mural for the people, but the representation of guns is also placed in the hands of the common people, giving them the power to overthrow dictatorship.

Other murals...

Rivera’s mural not only responds to the Revolution, but displays his political beliefs. Rivera was a “lifelong Marxist who belonged to the Mexican Communist Party and had important ties to the Soviet Union” [19]. “His art expressed his outspoken commitment to left-wing political causes” and El Arsenal or The Arsenal features the communist symbol of the hammer and sickle. Rivera’s personal beliefs supported the Revolution and, in this mural, the working class has power as an armed collective group. There are several long guns in this image as well as bullets and magazines. Guns are being distributed from the box on the bottom of the image and are being carried out of this arsenal. This image implies that guns were a necessary part of the Revolution to ensure the working class became heard. Like the organized militaries of the Americans and British, these Mexican revolutionaries have power in numbers and through their secretive supply of weapons. The distribution of power also extends to women and children, who have as much of an involvement in the war as their male counterparts. Like Delacroix, a child is also helping spread the guns and symbolizes the future of Mexico. It seems that Rivera is also implying the importance of the artist in war. He includes Frida Kahlo, a contemporary Mexican artist, in the center of the mural, who also holds a gun. The role of the artist extends beyond the artwork and sometimes even in the physical war. Rivera’s murals were often created in public spaces, so that they may be accessible to the common people. Not only was the mural for the people, but the representation of guns is also placed in the hands of the common people, giving them the power to overthrow dictatorship.

Other murals...

From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz to the Revolution, Diego Rivera

This mural shows Mexican soldiers, with zapatista clothing, showing their allegiance to Emiliano Zapata, a revolutionary leader [20].

The Future of History and Revolutionary Art

I have stopped my analysis at 1920; however, this excludes numerous wars before and after. The rise of technological advancements, especially with modern warfare, has transformed the use of guns in war. Revolutions still entail the use of weaponry to change the balance of power; however, muskets, which were the most common gun in my examples are now outdated. Guns have become more powerful and weapons like drones and tanks have improved the life of chances of soldiers; however, the damage that modern weaponry can inflict to masses of people has risen.

I have shown how across countries, the gun has been used to incite violence, to give power to the working class, and to protect citizen’s rights, to property, to free speech, to equality. Guns have been in the hands of individuals of different genders, races, ages, and nationalities and has therefore, been a symbol of equality. These paintings have presented the gun in a variety of lights, such as a heroic tool, a violent weapon, and a common object. In all of my examples, the gun has been a significant part of the figures’ identities, as revolutionaries and as combatants, and empowers them, in ways that may not be possible off the “battlefield.” The portrayal of the gun has ultimately complimented the notion of revolution, as a disruption of power.

The analysis of the paintings’ historical context and the motivations of the painter, shows how subjective art and history are. These paintings have helped shape our understanding of history and the role of the gun in war, and continues to change our associations of the gun. The political affiliations of different painters and their patrons has influenced the representation of battles, usually positively. I suspect that new artworks of history will continue to challenge the necessity for war and our perception of "heroes." A larger project may include modern artworks that respond to these historical pieces, as with my example of the Buffalo soldiers, to see how different nations regard the use of guns today. While the gun is a controversial tool, its been continually improved for war and recreational use, and this seems to be its trajectory for the future of war and art.

The analysis of the paintings’ historical context and the motivations of the painter, shows how subjective art and history are. These paintings have helped shape our understanding of history and the role of the gun in war, and continues to change our associations of the gun. The political affiliations of different painters and their patrons has influenced the representation of battles, usually positively. I suspect that new artworks of history will continue to challenge the necessity for war and our perception of "heroes." A larger project may include modern artworks that respond to these historical pieces, as with my example of the Buffalo soldiers, to see how different nations regard the use of guns today. While the gun is a controversial tool, its been continually improved for war and recreational use, and this seems to be its trajectory for the future of war and art.

Works Cited

1. Rabb, T; Brown, J. (1986). The Evidence of Art: Images and Meaning in History. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 17(1), 1-6. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/204122

2. Rabb, T. (2017). The Artist and the Warrior: Military History through the Eyes of the Masters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

3. Dickie, G. (1988). Evaluating Art. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

4. Jessup, B. (1968). The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26(3), 416-418. doi:10.2307/429153

5. Parker, D. (2002). Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition: In the West 1560-1991. London: Routledge.

6. Bellesiles, M. (2000). Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture. Brooklyn, NY: Softskull Press.

7. Liberty Leading the People. (2018). Britannica Online Academic Edition, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.

8. Hoffman, E. (1990). A FOOTNOTE TO EUGÈNE DELACROIX'S "LIBERTY LEADING THE PEOPLE". Source: Notes in the History of Art, 9(3), 24-30. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/stable/23202648

9. Wind, E. (1938). The Revolution of History Painting. Journal of the Warburg Institute, 2(2), 116-127.

10. Trumbull, J. (1775). The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/the-death-of-general-warren-at-the-battle-of-bunkers-hill-17-june-1775-34260. Oil on canvas. Text adapted from Elliot Bostwick Davis et al., (2003). American Painting, MFA Highlights [http://www.mfashop.com/9020398034.html]

11. Parmelee, K. (1993). John Trumbull: Heroic Male Nudity in the Enlightenment. Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 64-75. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40514354

12. Purcell, S. (2013). Martyred Blood and Avenging Spirits: Revolutionary Martyrs and Heroes as Inspiration for the U.S. Civil War. In McDonnell M., Corbould C., Clarke F., & Brundage W. (Eds.), Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation Making from Independence to the Civil War (pp. 280-293). University of Massachusetts Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk9zq.20

13. Ketchum, R. (1974). Decisive day; the battle for Bunker Hill. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

14. Binkin, M. (2011). Blacks and the Military. Brookings Institution Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=8EJow-Ni1BAC&lpg=PA1&ots=l46_jwg20_&dq=black%20soldiers%20in%20the%20battle%20of%20bunker%20hill&lr&pg=PA1#v=snippet&q=Bunker%20Hill&f=false

15. Sack, K. (2002). William Gilbert Gaul (American, 1855-1919). Tennessee Historical Quarterly, 61(1), 14-14. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/stable/42631050

16. Spanish-American War. (2018). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Spanish-American-War/68989

17. Smithsonian Museum. (2015, February 28). Buffalo Soldiers Legend and Legacy. Retrieved from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/manylenses/buffalosoldiers

18. PBS. History Detectives Special Investigations: Mexican Revolution. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/mexican-revolution/

19. Diego Rivera: Mexican Painter and Muralist. Retrieved from https://www.theartstory.org/artist-rivera-diego.htm

20. Andrews, A. (2010). Constructing Mutuality: The Zapatistas' Transformation of Transnational Activist Power Dynamics. Latin American Politics and Society, 52(1), 89-III.

-Stephanie Montalti

2. Rabb, T. (2017). The Artist and the Warrior: Military History through the Eyes of the Masters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

3. Dickie, G. (1988). Evaluating Art. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

4. Jessup, B. (1968). The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26(3), 416-418. doi:10.2307/429153

5. Parker, D. (2002). Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition: In the West 1560-1991. London: Routledge.

6. Bellesiles, M. (2000). Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture. Brooklyn, NY: Softskull Press.

7. Liberty Leading the People. (2018). Britannica Online Academic Edition, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.

8. Hoffman, E. (1990). A FOOTNOTE TO EUGÈNE DELACROIX'S "LIBERTY LEADING THE PEOPLE". Source: Notes in the History of Art, 9(3), 24-30. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/stable/23202648

9. Wind, E. (1938). The Revolution of History Painting. Journal of the Warburg Institute, 2(2), 116-127.

10. Trumbull, J. (1775). The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/the-death-of-general-warren-at-the-battle-of-bunkers-hill-17-june-1775-34260. Oil on canvas. Text adapted from Elliot Bostwick Davis et al., (2003). American Painting, MFA Highlights [http://www.mfashop.com/9020398034.html]

11. Parmelee, K. (1993). John Trumbull: Heroic Male Nudity in the Enlightenment. Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 64-75. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40514354

12. Purcell, S. (2013). Martyred Blood and Avenging Spirits: Revolutionary Martyrs and Heroes as Inspiration for the U.S. Civil War. In McDonnell M., Corbould C., Clarke F., & Brundage W. (Eds.), Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation Making from Independence to the Civil War (pp. 280-293). University of Massachusetts Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk9zq.20

13. Ketchum, R. (1974). Decisive day; the battle for Bunker Hill. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

14. Binkin, M. (2011). Blacks and the Military. Brookings Institution Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=8EJow-Ni1BAC&lpg=PA1&ots=l46_jwg20_&dq=black%20soldiers%20in%20the%20battle%20of%20bunker%20hill&lr&pg=PA1#v=snippet&q=Bunker%20Hill&f=false

15. Sack, K. (2002). William Gilbert Gaul (American, 1855-1919). Tennessee Historical Quarterly, 61(1), 14-14. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/stable/42631050

16. Spanish-American War. (2018). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Spanish-American-War/68989

17. Smithsonian Museum. (2015, February 28). Buffalo Soldiers Legend and Legacy. Retrieved from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/manylenses/buffalosoldiers

18. PBS. History Detectives Special Investigations: Mexican Revolution. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/mexican-revolution/

19. Diego Rivera: Mexican Painter and Muralist. Retrieved from https://www.theartstory.org/artist-rivera-diego.htm

20. Andrews, A. (2010). Constructing Mutuality: The Zapatistas' Transformation of Transnational Activist Power Dynamics. Latin American Politics and Society, 52(1), 89-III.

-Stephanie Montalti