GUNS in SOCIETY

Mass shootings and gun violence. What can be done?

In recent years barely a week goes by without reports of large scale gun violence, what we refer to as mass shootings. In the face of these continued assaults, and when confronted with issues of individual actions that affect broader society, we will instinctually withdraw and reflect on our own behavior. Then, as a group, we look to our institutions for answers, and take steps collectively to attempt to solve the problem.

Gun violence is an escalating and seemingly intractable epidemic in the US, and creating policy to address it has been politically difficult; often to the point of regression. Australia however, was able to respond to a pivotal mass shooting in 1996 with a comprehensive firearms control program, one that has now been in effect for over 20 years. Here we will look at the events that precipitated this ambitious effort, what changes were enacted, and examine the outcomes, both successful and not.

In recent years barely a week goes by without reports of large scale gun violence, what we refer to as mass shootings. In the face of these continued assaults, and when confronted with issues of individual actions that affect broader society, we will instinctually withdraw and reflect on our own behavior. Then, as a group, we look to our institutions for answers, and take steps collectively to attempt to solve the problem.

Gun violence is an escalating and seemingly intractable epidemic in the US, and creating policy to address it has been politically difficult; often to the point of regression. Australia however, was able to respond to a pivotal mass shooting in 1996 with a comprehensive firearms control program, one that has now been in effect for over 20 years. Here we will look at the events that precipitated this ambitious effort, what changes were enacted, and examine the outcomes, both successful and not.

|

The Tragedy

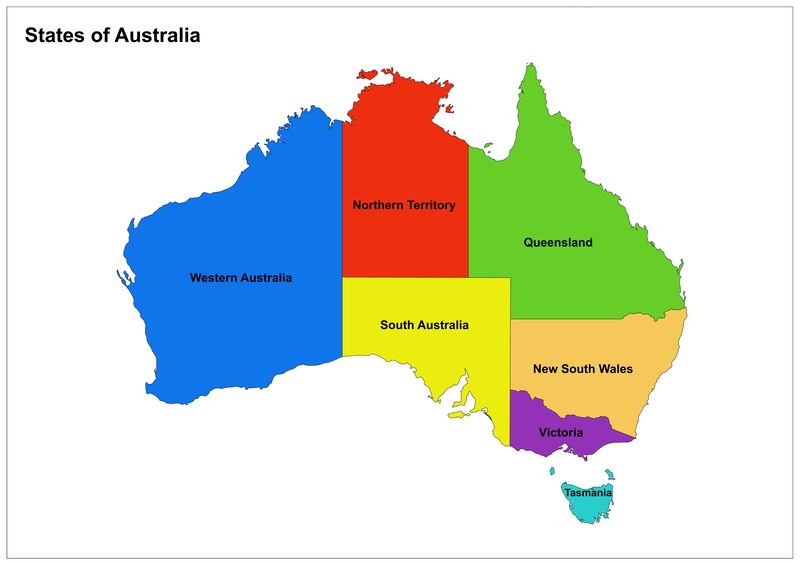

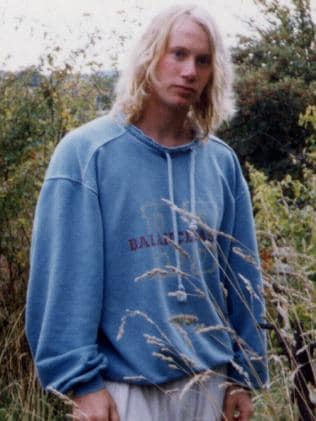

On Sunday April 28 1996, 28 year old Martin Bryant entered the Port Arthur Historic Site, a popular tourist destination in Tasmania, South Eastern Australia, on the remains of an 1830 penal colony. After calmly eating lunch in the café, he removed one of 2 AR-15 type military rifles from a duffel bag he was carrying and began methodically shooting at tourists, many of them families with young children. Over the next few minutes he would kill 23 and wound 18 others, then escape to a home where he had earlier killed the couple inside. After a police standoff, and setting both the home and himself on fire, he was captured. The Port Arthur Massacre, as it came to be called, was the largest single-shooter mass shooting in Australian history. The 35 total people killed represented more than half the nation’s average total gun homicides per year, and more than the entire yearly total for the Tasmanian state 1 Bryant, who reportedly laughed aggressively during the rampage, had no prior arrests, nor any record of mental illness, though was considered disabled due to low mental capacity/IQ 2 The shooter notably killed 22 victims in minutes, with only 29 shots, a commentary on both the deliberate nature of the act, and intrinsic, efficient lethality of the weapon(s) used. 3 |

|

Response to the tragedy was immediate and culturally encompassing. Tasmania is a small island state, quiet and rural, and the shattering Sunday afternoon massacre gripped national headlines immediately and for weeks thereafter.

Calls for action were intense and broad based, and public sentiment for gun control was very high, with opinion polling showing 92%+ public support 4

At the time of the killings Australia had a newly elected Prime Minister, John Howard, who had been in office barely 2 months. Howard, a conservative, was visibly affected by the horror of the event and pledged immediate action, which began at the very first assembled seating of his government the next morning.

In less than 2 weeks, Howard and attorney general Daryll Wilson would craft, and have a bipartisan parliament pass, a comprehensive gun bill that had both regulations and reach never before attempted in Australia. Prime Minister Howard's unwavering commitment to immediate and real change was key to having his normally pro gun rights party support the reforms.

The legislation was presented to and approved at a meeting of the Australian Prime Ministers Council on May 10, 1996, with all 6 Australian states and 2 territories in agreement.

Calls for action were intense and broad based, and public sentiment for gun control was very high, with opinion polling showing 92%+ public support 4

At the time of the killings Australia had a newly elected Prime Minister, John Howard, who had been in office barely 2 months. Howard, a conservative, was visibly affected by the horror of the event and pledged immediate action, which began at the very first assembled seating of his government the next morning.

In less than 2 weeks, Howard and attorney general Daryll Wilson would craft, and have a bipartisan parliament pass, a comprehensive gun bill that had both regulations and reach never before attempted in Australia. Prime Minister Howard's unwavering commitment to immediate and real change was key to having his normally pro gun rights party support the reforms.

The legislation was presented to and approved at a meeting of the Australian Prime Ministers Council on May 10, 1996, with all 6 Australian states and 2 territories in agreement.

The National Firearms Agreement, as It came to be known, was the largest federal level gun control law ever passed in Australia. Like the US, Australia is a federation of states; federal laws need to be ratified by, and are sometimes rejected or re-interpreted by individual states.

The key items of the Agreement are listed below:

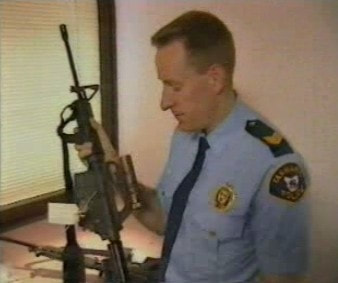

1. A complete prohibition on self-loading (semi automatic) weapons of all types. This included center-fire, and smaller bore rim-fire rifles, whether military spec or not. It also included both self loading and pump action shotguns.

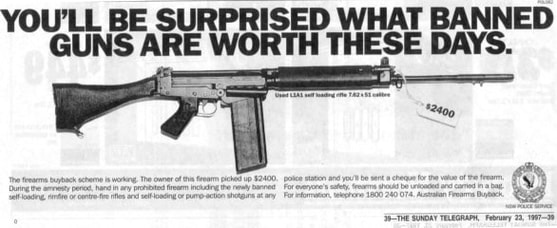

2. A national buyback program where gun owners would have a 12 month period of unconditional amnesty; and the government would pay full retail value for any of the newly illegal firearms.

3. The registration of all firearms, with a national computerized database kept by/for police forces. Sales only allowed from licensed dealers.

4. Licensing for all gun ownership required nationwide, with licensing granted on a per single gun basis; and only by demonstrated need, a “specific reason”. Licenses limited to maximum 5 year periods

.

5. Mandatory 28 day waiting period on any gun purchase.

6. Training a requirement for any licensing

7. Strict and standardized gun storage requirements

8. Ammunition also regulated and only legally sold to licensed gun owners

The key items of the Agreement are listed below:

1. A complete prohibition on self-loading (semi automatic) weapons of all types. This included center-fire, and smaller bore rim-fire rifles, whether military spec or not. It also included both self loading and pump action shotguns.

2. A national buyback program where gun owners would have a 12 month period of unconditional amnesty; and the government would pay full retail value for any of the newly illegal firearms.

3. The registration of all firearms, with a national computerized database kept by/for police forces. Sales only allowed from licensed dealers.

4. Licensing for all gun ownership required nationwide, with licensing granted on a per single gun basis; and only by demonstrated need, a “specific reason”. Licenses limited to maximum 5 year periods

.

5. Mandatory 28 day waiting period on any gun purchase.

6. Training a requirement for any licensing

7. Strict and standardized gun storage requirements

8. Ammunition also regulated and only legally sold to licensed gun owners

g.

g.

The buyback

The key element of the NFA was a year long national amnesty and buyback for the newly prohibited firearms. Beginning on October 1, 1996 the program offered fair market value (as of March 1996) for all self loading (semi automatic), long guns including military spec (assault rifles). It also included pump action shotguns. This generous compensation plan was actually mandated, as the Australian Constitution requires full (retail) compensation on any government seizure of property. 5

The program was funded through a one time, 0.2 percent assessment to the Medicare tax. Ending on September 30, 1997, the program, celebrated in media as "The Big Melt" collected over 640,000 banned guns, and total compensation to owners was approximately $300 million. 6

The key element of the NFA was a year long national amnesty and buyback for the newly prohibited firearms. Beginning on October 1, 1996 the program offered fair market value (as of March 1996) for all self loading (semi automatic), long guns including military spec (assault rifles). It also included pump action shotguns. This generous compensation plan was actually mandated, as the Australian Constitution requires full (retail) compensation on any government seizure of property. 5

The program was funded through a one time, 0.2 percent assessment to the Medicare tax. Ending on September 30, 1997, the program, celebrated in media as "The Big Melt" collected over 640,000 banned guns, and total compensation to owners was approximately $300 million. 6

Gun Reduction

The Australian experiment with gun regulation and voluntary surrender has been watched closely and analyzed since its inception. Now some 20+ years later we can look at outcomes on a significant timeline and draw some conclusions on the law and its efficacy.

Let's start with actual gun reduction: Since the 1996 Federal buyback, there have been some 38 state and federal purchase and/or amnesty programs throughout Australia. They have by conservative estimates, resulted in the acquisition and subsequent destruction of over a million firearms. 7

The 600,000 + guns surrendered in the 1996 buyback alone represented over a fifth of all the guns in circulation, an astounding reduction that would be the equivalent of 40 million guns in the United States.8 Indeed, the million plus total recovered through 2016 is almost a third of the total guns in circulation.

The Australian experiment with gun regulation and voluntary surrender has been watched closely and analyzed since its inception. Now some 20+ years later we can look at outcomes on a significant timeline and draw some conclusions on the law and its efficacy.

Let's start with actual gun reduction: Since the 1996 Federal buyback, there have been some 38 state and federal purchase and/or amnesty programs throughout Australia. They have by conservative estimates, resulted in the acquisition and subsequent destruction of over a million firearms. 7

The 600,000 + guns surrendered in the 1996 buyback alone represented over a fifth of all the guns in circulation, an astounding reduction that would be the equivalent of 40 million guns in the United States.8 Indeed, the million plus total recovered through 2016 is almost a third of the total guns in circulation.

h.

h.

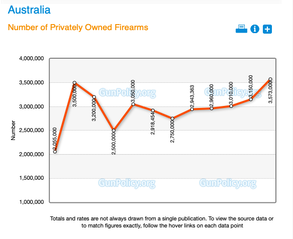

Critics and anti gun control advocates have often noted that despite the broad reduction in banned firearms, a significant amount of "replacement buying" has occurred. After an initial period of decline, the total amount of guns in use in Australia today now has met and slightly exceeded the amount just before the law was enacted in 1996. However, none of these guns are semi-automatic, large magazine and/or military spec rifles, which are still completely banned and unavailable legally. These guns are single shot/chambering and not of the rapid fire type from before 1996. 9

i.

i.

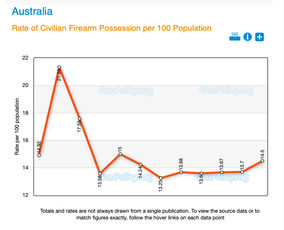

In addition, while gun totals are at 1996 levels, the total population has risen 35% from 18 to 25 million. This is important as it shows that the rate of firearm use actually has truly dropped and stabilized, attaining a new and significantly lower status quo.

j.

j.

Gun reduction sentiment was not just a reactionary moment adjacent to the 1996 event, it has become an accepted part of Australian culture.

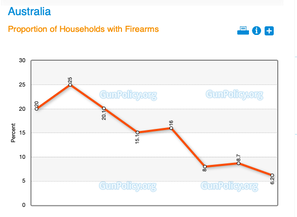

As late as 1980 some 20 percent of Australian households had at least one gun; today it has dropped to less than 6 percent. 10

As late as 1980 some 20 percent of Australian households had at least one gun; today it has dropped to less than 6 percent. 10

k.

k.

Gun Violence

The actual numbers of guns reduced by the NFA, and in particular the type and lethality were of course significant. We can also look at gun violence and crime in the two decades since The Port Arthur shooting.

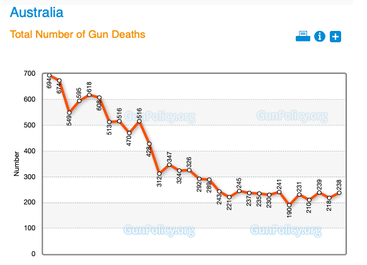

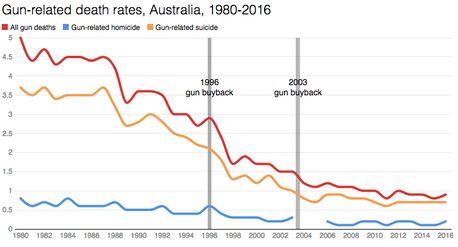

The first and broadest metric to examine would be total gun related deaths. Gun deaths have declined steadily in the years since enactment of the National Firearms Agreement. In 1996, the year of the massacre, there were 516 gun deaths. Even with that event-related uptick, there was a trend downward in gun violence that had begun in the 1980's . Statistically the rate had been dropping at around 3% per year, but accelerated to a rate of 7.5 % per year after enactment of the NFA. 11

The actual numbers of guns reduced by the NFA, and in particular the type and lethality were of course significant. We can also look at gun violence and crime in the two decades since The Port Arthur shooting.

The first and broadest metric to examine would be total gun related deaths. Gun deaths have declined steadily in the years since enactment of the National Firearms Agreement. In 1996, the year of the massacre, there were 516 gun deaths. Even with that event-related uptick, there was a trend downward in gun violence that had begun in the 1980's . Statistically the rate had been dropping at around 3% per year, but accelerated to a rate of 7.5 % per year after enactment of the NFA. 11

l.

l.

What is significant is that the tragedy and the subsequent legislation and buyback produced an immediate and profound behavioral change, accelerating the drop in deaths and re-setting the trend line. 12

All gun related deaths have decreased. Symbolically important is that there has has not been a single mass shooting (4 or more persons) since the NFA was enacted in 1996.

All gun related deaths have decreased. Symbolically important is that there has has not been a single mass shooting (4 or more persons) since the NFA was enacted in 1996.

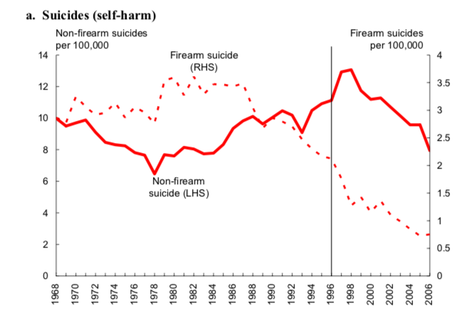

While homicide rates, regardless of method, had been declining for many years, suicide rates were not. However, In the decades since the buyback and enactment of NFA restrictions gun related suicides dropped profoundly. Firearm suicides dropped from a rate of 3.4 per 100,000 in 1995 to 0.8 per 100,000 in 2005 a 59% drop.

Non firearm suicides dropped from a rate of 19.9 per 100,000 to 15.0, a 14% decline, which demonstrates that there was only a nominal substitution. 13

Non firearm suicides dropped from a rate of 19.9 per 100,000 to 15.0, a 14% decline, which demonstrates that there was only a nominal substitution. 13

m.

m.

While there is evidence of some "substitution effect", where other means are used to carry out suicide, the rate change and reduced lasting levels of firearm use are documented and profound. The immediate and catastrophic consequences of gun availability in cases of suicidal depression are always cited as a reason for access control. Guns are the primary method of suicide in most countries but this is no longer the case in Australia. 14

n.

n.

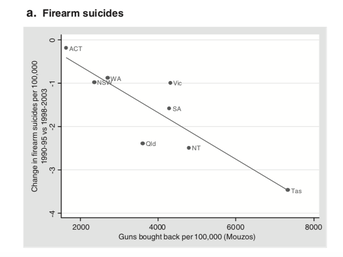

Even the regional variances in the success of the 1996-1997 buyback had correlation to gun-suicide reduction. The rate of firearm suicide dropped greatest in states/territories that reclaimed/recovered the most guns. 15

Conclusions

The National Firearms Agreement has been shown to be one of the most successful firearm control programs in modern history. Inspired by an all too common tragedy of mass shooting, the citizenry and government aligned to create a comprehensive and unified set of regulations, with a goal of reducing gun crime and harm. Key to its passage was strong and unwavering political leadership, and (after years of failures) a population that was adamant that their government act decisively. With the NFA the government did just that, crafting and passing the legislation in less than 2 weeks.

The NFA contained far reaching and coordinated regulations, including a complete ban on semi automatic, rapid fire weapons. Where contradictory and lax gun regional gun regulation existed before, Australia now has coordinated registration amongst its states, a national database, and an effective national program of required training and licensing for citizens that wish to own firearms. At the same time of this legislation, Australia also began the largest and most successful amnesty and buyback program in history, ultimately recovering and destroying over 1 million illegal guns.

This profound change in the gun environment and culture has yielded positive results. Gun related crime, gun homicides, and the often ignored but more significant amount of gun suicides have all dropped by significant measurable amounts, and these reductions in harm have continued for over 2 decades. While gun totals have gradually risen, all of these firearms are now much safer single fire and low capacity design. The actions of the Australian Government, in reflecting the will of its citizenry, has not only been effective law; after 22 years it represents a lasting change to the culture and an affirmation of sensible gun regulation in a modern society.

The National Firearms Agreement has been shown to be one of the most successful firearm control programs in modern history. Inspired by an all too common tragedy of mass shooting, the citizenry and government aligned to create a comprehensive and unified set of regulations, with a goal of reducing gun crime and harm. Key to its passage was strong and unwavering political leadership, and (after years of failures) a population that was adamant that their government act decisively. With the NFA the government did just that, crafting and passing the legislation in less than 2 weeks.

The NFA contained far reaching and coordinated regulations, including a complete ban on semi automatic, rapid fire weapons. Where contradictory and lax gun regional gun regulation existed before, Australia now has coordinated registration amongst its states, a national database, and an effective national program of required training and licensing for citizens that wish to own firearms. At the same time of this legislation, Australia also began the largest and most successful amnesty and buyback program in history, ultimately recovering and destroying over 1 million illegal guns.

This profound change in the gun environment and culture has yielded positive results. Gun related crime, gun homicides, and the often ignored but more significant amount of gun suicides have all dropped by significant measurable amounts, and these reductions in harm have continued for over 2 decades. While gun totals have gradually risen, all of these firearms are now much safer single fire and low capacity design. The actions of the Australian Government, in reflecting the will of its citizenry, has not only been effective law; after 22 years it represents a lasting change to the culture and an affirmation of sensible gun regulation in a modern society.

1. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Gun Homicides. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 8 December 2018. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/number_of_gun_homicides

2. Chapman, S. (2013). Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s fight for gun control. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

3.Altmann, Carol. 2006 After Port Arthur : personal stories of courage and resilience ten years on from the tragedy that shocked the nation. Crows Nest, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin.

4..Chapman, S. (2013). Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s fight for gun control. Sydney: Sydney University Press. p33

5.Chapman, S., Alpers, P., & Jones, M. (2016). Association Between Gun Law Reforms and Intentional Firearm Deaths in Australia, 1979-2013. JAMA, 316(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8752

6. Australian National Audit Office, Reeve, G., & Lewis, M. (1997). The gun buy-back scheme: Attorney-General’s Department. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office.

7 .Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; Part IV, Chapter 16, pp. 207-208.

8. Reuter, Peter and Jenny Mouzos. 2003. “Australia: A massive buyback of low-risk guns.” In Jens Ludwig and Philip J. Cook (eds.), Evaluating Gun Policy: Effects on Crime and Violence. (pp.121-156). Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press

9.. Leigh, A., & Neill, C. (2010). Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1631130). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1631130

9 Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; Part IV, Chapter 16,

11. Chapman, S., Alpers, P., & Jones, M. (2016). Association Between Gun Law Reforms and Intentional Firearm Deaths in Australia, 1979-2013. JAMA, 316(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8752

12. Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; Part IV, Chapter 16,

13. .Chapman, S. (2013). Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s fight for gun control. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

14.. Leigh, A., & Neill, C. (2010). Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1631130). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1631130

15..Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1631130

2. Chapman, S. (2013). Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s fight for gun control. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

3.Altmann, Carol. 2006 After Port Arthur : personal stories of courage and resilience ten years on from the tragedy that shocked the nation. Crows Nest, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin.

4..Chapman, S. (2013). Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s fight for gun control. Sydney: Sydney University Press. p33

5.Chapman, S., Alpers, P., & Jones, M. (2016). Association Between Gun Law Reforms and Intentional Firearm Deaths in Australia, 1979-2013. JAMA, 316(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8752

6. Australian National Audit Office, Reeve, G., & Lewis, M. (1997). The gun buy-back scheme: Attorney-General’s Department. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office.

7 .Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; Part IV, Chapter 16, pp. 207-208.

8. Reuter, Peter and Jenny Mouzos. 2003. “Australia: A massive buyback of low-risk guns.” In Jens Ludwig and Philip J. Cook (eds.), Evaluating Gun Policy: Effects on Crime and Violence. (pp.121-156). Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press

9.. Leigh, A., & Neill, C. (2010). Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1631130). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1631130

9 Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; Part IV, Chapter 16,

11. Chapman, S., Alpers, P., & Jones, M. (2016). Association Between Gun Law Reforms and Intentional Firearm Deaths in Australia, 1979-2013. JAMA, 316(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8752

12. Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; Part IV, Chapter 16,

13. .Chapman, S. (2013). Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s fight for gun control. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

14.. Leigh, A., & Neill, C. (2010). Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1631130). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1631130

15..Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1631130

Graphics citations

a. https://mapuniversal.com/australian-states-territories/

b. https://www.touringtasmania.info/port_arthur_historic_site.htm

c. https://cdn.newsapi.com.au/image/v1/3ad77798f1bd2c843fb81ea509123790?width=316

d. http://www.geniac.net/portarthur/images/cafe.jpg

e. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3562751/Harrowing-photos-Port-Arthur-massacre-unfolded-20-years-ago.html

f. Source: http://members.iinet.net.au/~nedwood/Dutton_AR15_2.jpg

g.Source: http://members.iinet.net.au/~nedwood/gun%20ad.jpg

h. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Number of Privately Owned Firearms. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 9 December 2018. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/number_of_privately_owned_firearms

i. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Rate of Civilian Firearm Possession per 100 Population. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 9 December 2018. at https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/rate_of_civilian_firearm_possession

k. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Proportion of Households with Firearms.Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 9 December 2018. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/proportion_of_households_with_firearms

l. “Did Government Gun Buybacks Reduce the Number of Gun Deaths in Australia?” https://indaily.com.au/news/sponsored-content/2017/11/10/fact-check-government-gun-buybacks-reduce-number-gun-deaths-australia/ (December 8, 2018).

m. Leigh, A., and C. Neill. 2010. “Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data.” American Law and Economics Review 12(2): 509–57. https://academic.oup.com/aler/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/aler/ahq013(December 4, 2018).

n. Leigh, A., and C. Neill. 2010. “Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data.” American Law and Economics Review 12(2): 509–57. https://academic.oup.com/aler/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/aler/ahq013(December 4, 2018).

a. https://mapuniversal.com/australian-states-territories/

b. https://www.touringtasmania.info/port_arthur_historic_site.htm

c. https://cdn.newsapi.com.au/image/v1/3ad77798f1bd2c843fb81ea509123790?width=316

d. http://www.geniac.net/portarthur/images/cafe.jpg

e. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3562751/Harrowing-photos-Port-Arthur-massacre-unfolded-20-years-ago.html

f. Source: http://members.iinet.net.au/~nedwood/Dutton_AR15_2.jpg

g.Source: http://members.iinet.net.au/~nedwood/gun%20ad.jpg

h. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Number of Privately Owned Firearms. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 9 December 2018. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/number_of_privately_owned_firearms

i. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Rate of Civilian Firearm Possession per 100 Population. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 9 December 2018. at https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/rate_of_civilian_firearm_possession

k. Alpers, Philip, Amélie Rossetti and Mike Picard. 2018. Guns in Australia: Proportion of Households with Firearms.Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. GunPolicy.org, 3 October. Accessed 9 December 2018. at: https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/compareyears/10/proportion_of_households_with_firearms

l. “Did Government Gun Buybacks Reduce the Number of Gun Deaths in Australia?” https://indaily.com.au/news/sponsored-content/2017/11/10/fact-check-government-gun-buybacks-reduce-number-gun-deaths-australia/ (December 8, 2018).

m. Leigh, A., and C. Neill. 2010. “Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data.” American Law and Economics Review 12(2): 509–57. https://academic.oup.com/aler/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/aler/ahq013(December 4, 2018).

n. Leigh, A., and C. Neill. 2010. “Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data.” American Law and Economics Review 12(2): 509–57. https://academic.oup.com/aler/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/aler/ahq013(December 4, 2018).

Bibliography:

Books:

1. Chapman, Simon. 2013. Over Our Dead Bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s Fight for Gun Control. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

2. Altmann, Carol. 2006 After Port Arthur : personal stories of courage and resilience ten years on from the tragedy that shocked the nation. Crows Nest, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin.

Journal Articles:

3. Chapman, S., P. Alpers, K. Agho, and M. Jones. 2006. “Australia’s 1996 Gun Law Reforms: Faster Falls in Firearm Deaths, Firearm Suicides, and a Decade without Mass Shootings.” Injury Prevention 12 (6): 365–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2006.013714.

4. Chapman, Simon, et al. “Association Between Gun Law Reforms and Intentional Firearm Deaths in Australia, 1979-2013.” JAMA, vol. 316, no. 3, July 2016, pp. 291–99, doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8752.

5. Taylor, Benjamin, and Jing Li. “Do Fewer Guns Lead to Less Crime? Evidence from Australia.” International Review of Law and Economics, vol. 42, 2015, pp. 72–78, doi:10.1016/j.irle.2015.01.002.

6. Leigh, Andrew, and Christine Neill. “Do Gun Buybacks Save Lives? Evidence from Panel Data.” American Law and Economics Review, vol. 12, no. 2, Oct. 2010, pp. 509–57, doi:10.1093/aler/ahq013.

7. Hemenway, David. “How to Find Nothing.” Journal of Public Health Policy, vol. 30, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 260–68, doi:10.1057/jphp.2009.26.

8. Reuter and Mouzos - Australia A Massive Buy back of Low-Risk Guns.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/526a/200e5586c3feaf984027fed9106ff5941a81.pdf

9. Alpers, Philip. 2013 ‘The Big Melt: How One Democracy Changed after Scrapping a Third of Its Firearms - Fall in Gun Violence.’ Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis; . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Web Page:

8. Criminology; Australian Institute of. “Trends in Homicide, 1980-90 to 201314.”CrimeStatisticsAustralia,” http://crimestats.aic.gov.au/NHMP/1_tr ends/index.html. Accessed 10 Nov. 2018.